Table of Contents

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – J.K. Rowling Writes

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was a phenomenal success in 2001 – Here are some great insights into the creation of the book and movie!

Even though Harry Potter strolled into Rowling’s head fully formed, she still spent several years outlining the seven books, and then she spent another year writing the first one, Harry Potter and Sorcerer’s Stone.

Rowling rewrote chapter one of Sorcerer’s Stone so many times (upwards of fifteen discarded drafts) that her first attempts “bear no resemblance to anything in the finished book.” This was especially frustrating for Rowling because she was a single parent and her writing time was both limited and sporadic—entirely contingent on her infant daughter, Jessica.

Whenever Jessica fell asleep in her [stroller], I would dash to the nearest café and write like mad. I wrote nearly every evening. Then I had to type the whole thing out myself. Sometimes I actually hated the book, even while I loved it.

Rowling had to deal with many other time-wasting nuisances, like re-typing an entire chapter because she had changed one paragraph, and then re-typing the entire manuscript because she hadn’t double-spaced it.

Rowling also struggled with personal problems while writing the first book:

the death of her mother,

estrangement from her father,

a volatile and short-lived marriage,

a newborn child,

life on welfare,

and a battle with clinical depression.

To top it off, Rowling’s support system was pretty much nonexistent. She struggled with suicidal thoughts and eventually turned to therapy for help. Rowling once told a friend about her book idea and her friend’s response was cynical. Rowling said:

I think she thought I was deluding myself, that I was in a nasty situation and had sat down one day and thought, I know, I’ll write a novel. She probably thought it was a get-rich-quick scheme.

Once the manuscript was finally finished, Rowling went on to collect a dozen rejection letters over the span of a year before Bloomsbury Publishing agreed to pick it up.

Even with publication now on the horizon, though, Rowling was warned by her literary agent to find a job because her story wasn’t commercial enough to be successful (“You do realize, you will never make a fortune out of writing children’s books?”). In fact, Bloomsbury’s expectations of the first Potter book were so low that its initial print was only five hundred copies—three hundred of which were donated to public libraries. Rowling’s first royalty check was six hundred pounds.

A year later, she was a millionaire.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – To Book

Scholastic Corporation bought the US rights at the Bologna Book Fair in April 1997 for US$105,000, an unusually high sum for a children’s book. Scholastic’s Arthur Levine thought that “philosopher” sounded too archaic for readers and after some discussion (including the proposed title “Harry Potter and the School of Magic”), the American edition was published in September 1998 under the title Rowling suggested, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Rowling later said that she regretted this change and would have fought it if she had been in a stronger position at the time. Philip Nel has pointed out that the change lost the connection with alchemy and the meaning of some other terms changed in translation, for example from “crumpet” to “muffin”.

While Rowling accepted the change from both the British English “mum” and Seamus Finnigan’s Irish variant “mam” to the American variant “mom” in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, she vetoed this change in the later books, which was then reversed in later editions of Philosopher’s Stone. However, Nel considered that Scholastic’s translations were considerably more sensitive than most of those imposed on British English books of the time and that some other changes could be regarded as useful copyedits.

Since the UK editions of early titles in the series were published months prior to the American versions, some American readers became familiar with the British English versions owing to having bought them from online retailers.

At first the most prestigious reviewers ignored the book, leaving it to book trade and library publications such as Kirkus Reviews and Booklist, which examined it only by the entertainment-oriented criteria of children’s fiction. However, more penetrating specialist reviews (such as one by Cooperative Children’s Book Center Choices, which noted complexity, depth and consistency in the world that Rowling had built) attracted the attention of reviewers in major newspapers.

Although The Boston Globe and Michael Winerip in The New York Times complained that the final chapters were the weakest part of the book, they and most other American reviewers gave glowing praise. A year later, the US edition was selected as an American Library Association Notable Book, a Publishers Weekly Best Book of 1998 and a New York Public Library 1998 Best Book of the Year and won Parenting Magazine’s Book of the Year Award for 1998, the School Library Journal Best Book of the Year and the American Library Association Best Book for Young Adults. In 2012 it was ranked number 3 on a list of the top 100 children’s novels published by School Library Journal.

In August 1999, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone topped the New York Times list of best-selling fiction and stayed near the top of the list for much of 1999 and 2000, until the New York Times split its list into children’s and adult sections under pressure from other publishers who were eager to see their books given higher placings. Publishers Weekly’s report in December 2001 on cumulative sales of children’s fiction placed Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone 19th among hardbacks (over 5 million copies) and 7th among paperbacks (over 6.6 million copies).

In May 2008, Scholastic announced the creation of a 10th Anniversary Edition of the book that was released on 1 October 2008 to mark the tenth anniversary of the original American release. For the fifteenth anniversary of the books, Scholastic re-released Sorcerer’s Stone, along with the other six novels in the series, with new cover art by Kazu Kibuishi in 2013.

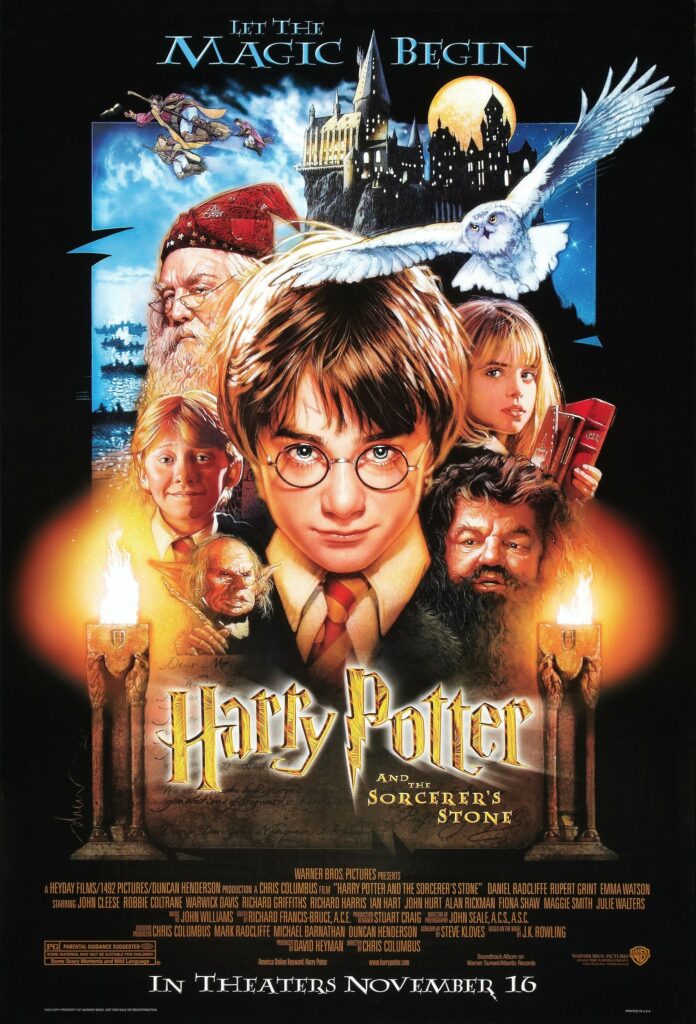

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – To Movie

”Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” is a red-blooded adventure movie, dripping with atmosphere, filled with the gruesome and the sublime, and surprisingly faithful to the novel. A lot of things could have gone wrong, and none of them have: Chris Columbus’ movie is an enchanting classic that does full justice to a story that was a daunting challenge.

The novel by J.K. Rowling was muscular and vivid, and the danger was that the movie would make things too cute and cuddly. It doesn’t. Like an “Indiana Jones” for younger viewers, it tells a rip-roaring tale of supernatural adventure, where colorful and eccentric characters alternate with scary stuff like a three-headed dog, a pit of tendrils known as the Devil’s Snare and a two-faced immortal who drinks unicorn blood. Scary, yes, but not too scary–just scary enough.

Three high-spirited, clear-eyed kids populate the center of the movie. Daniel Radcliffe plays Harry Potter, he with the round glasses, and like all of the young characters he looks much as I imagined him, but a little older. He once played David Copperfield on the BBC, and whether Harry will be the hero of his own life in this story is much in doubt at the beginning.

Deposited as a foundling on a suburban doorstep, Harry is raised by his aunt and uncle as a poor relation, then summoned by a blizzard of letters to become a student at Hogwarts School, an Oxbridge for magicians. Our first glimpse of Hogwarts sets the tone for the movie’s special effects. Although computers can make anything look realistic, too much realism would be the wrong choice for “Harry Potter,” which is a story in which everything, including the sets and locations, should look a little made up.

The school, rising on ominous Gothic battlements from a moonlit lake, looks about as real as Xanadu in “Citizen Kane,” and its corridors, cellars and great hall, although in some cases making use of real buildings, continue the feeling of an atmospheric book illustration. At Hogwarts, Harry makes two friends and an enemy. The friends are Hermione Granger (Emma Watson), whose merry face and tangled curls give Harry nudges in the direction of lightening up a little, and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint), all pluck, luck and untamed talents. The enemy is Draco Malfoy (Tom Felton), who will do anything, and plenty besides, to be sure his house places first at the end of the year.

The story you either already know, or do not want to know. What is good to know is that the adult cast, a who’s who of British actors, play their roles more or less as if they believed them. There is a broad style of British acting, developed in Christmas pantomimes, which would have been fatal to this material; these actors know that, and dial down to just this side of too much.

Watch Alan Rickman drawing out his words until they seem ready to snap, yet somehow staying in character. Maggie Smith, still in the prime of Miss Jean Brodie, is Prof. Minerva McGonagall, who assigns newcomers like Harry to one of the school’s four houses. Richard Harris is headmaster Dumbledore, his beard so long that in an Edward Lear poem, birds would nest in it. Robbie Coltrane is the gamekeeper, Hagrid, who has a record of misbehavior and a way of saying very important things and then not believing that he said them.

Computers are used, exuberantly, to create a plausible look in the gravity-defying action scenes. Readers of the book will wonder how the movie visualizes the crucial game of Quidditch. The game, like so much else in the movie, is more or less as I visualized it, and I was reminded of Stephen King’s theory that writers practice a form of telepathy, placing ideas and images in the heads of their readers. (The reason some movies don’t look like their books may be that some producers don’t read them.)

If Quidditch is a virtuoso sequence, there are other set pieces of almost equal wizardry. A chess game with life-size, deadly pieces. A room filled with flying keys. The pit of tendrils, already mentioned, and a dark forest where a loathsome creature threatens Harry but is scared away by a centaur. And the dark shadows of Hogwarts library, cellars, hidden passages and dungeons, where an invisibility cloak can keep you out of sight but not out of trouble.

During “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” I was pretty sure I was watching a classic, one that will be around for a long time, and make many generations of fans. It takes the time to be good. It doesn’t hammer the audience with easy thrills, but cares to tell a story, and to create its characters carefully. Like “The Wizard of Oz,” “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” “Star Wars” and “E.T.,” it isn’t just a movie but a world with its own magical rules. And some excellent Quidditch players.

For More Harry Potter Fandom – Follow This Link…

To Return to Our Main Halloween Site – Follow This Link…

The All Halloween Website – (celebratehalloween.net)